PM Modi’s announcement of a national museum, ‘Yuge Yugeen Bharat’, derived from Sanskrit, which means ‘everlasting India’, is set to become the world’s largest museum.

Postcolonial India has largely demonstrated a distrust, even disengagement with its own rich cultural heritage. Driven by its blind race to become modern, it continued to shun and erase the magnanimity of India’s ancient history and cultural diversity. As a nation, we started rebuilding India with borrowed ideas from our colonial masters, the signs of our political leaders’ fascination with white colour and white structures.

Nehruvian modernity came at the cost of sacrificing India’s vibrant, multicultural history. The scaffolding of our postcolonial nation was devoid of its past artifacts, thus leading us to a point where neither the younger generation demonstrated much awareness of their country’s history, nor they were fully modern. As it turned out, the drive to modernity produced a class that was historically and culturally ignorant and pessimist, energised as they were by the colonial hangover and the dreams of a eulogising career in the West.

India has many histories. Neither I contest this fact, nor do I wish to labour on this point. The point of contestation, however, is the selective amnesia to India’s civilisational heritage and acute hypnotism to knowledge systems that critiqued and questioned the idea of India, demonstrated by many Western-trained academicians, writers, and activists. “They undervalued and consciously rejected many of the achievements of ancient India,” as pointed out by the academician, Rakesh Sinha.

Disowned and gatekept by the “barahmasi” historians and ideologues, whose only expertise lies in critiquing, shaming, and even questioning India’s past, it is no wonder that we witness a gripping control over the postcolonial Indian society by an immutable ideological leaning, which continues to breathe and thrive by raising rhetoric of “unsafe India” and “democracy in danger”. The irony is our ancient practices and culture account for myths and superstitions, while the future-building exercise driven by the “barahmasi” prejudiced group is underpinned with the whiffs of Western modernity.

The implications of this aspersion and suspicion are the appropriation, promotion, and even

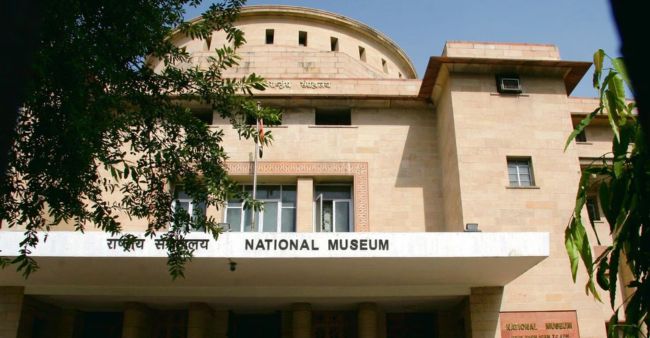

The story of our truncated history must give way to a collective future and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement of a national museum, “Yuge Yugeen Bharat”—derived from Sanskrit, which means “everlasting India”—that is set to become the world’s largest museum, comprising eight thematic segments, and projecting India’s history spanning over 5,000 years. This museum will be built in Delhi, covering “an area of 1.17 lakh sqm with 950 rooms spread over a basement and three storeys”. Evidently, this will be bigger than the British Museum in London and the Grand Louvre in Paris, which covers around 70,000 square metres. The museum is all set to highlight the contributions of indigenous freedom fighters, the forgotten faces in our history. One will also engage with the ancient town planning systems in India, the contributions of ancient medical knowledge, the Vedas and Upanishads, while also focusing on the period from the Mauryan to Gupta Empires, Vijayanagara Empire, Mughal Empire, and other dynasties.

This move has already ruffled the self-declared custodians of India’s history, who have started questioning this new museum’s need by offering a damning critique of India’s nationalism and positing the usual semiotics of hatred towards the present regime, mourning the unchecked rise of Hindutva, and underlining India’s weak economy—the usual vocabulary of the barahmasi figures.

As records suggest, these criticisms have only strengthened PM Modi’s moves and his position both in India and on the global front. He has been singularly determined to conjoin the wisdom of India’s past with the modern temper, realising the need for this fusion to rebuild a strong, confident, self-reliant nation. This has ensured that national history is not determined by a group of elites, “woke faculty”, or an ideologically homogenous community. Rather, the new museum is democratically mediated since it aims to uphold and promote the diversity of the rich Indian knowledge system, while also stoking it with the fuel of modernity.

If “India is poised to shape a new order in the 21st century… and become a laboratory for global good” as the Education Minister Dharmendra Pradhan suggests, then “democracy, demography, and diversity” will continue to be its strengths. The new museum will serve in this direction by instilling a sense of confidence in our youths. It will be good if “museum visits” can be a part of our school-level curriculum. Museums are integral to our cultural imaginations. They foreground a sense of ontological and epistemological commitments.

The museum “rejects no new light”, but it will aim to promote our cultural diversity and richness. The rub of the matter is nation building requires its past to design the pathway of futurity. Museum visits can render this new orientation and understanding to our young generation, making them aware that it is vital “to look into our own backyards’ to ‘think big and act big.”

- Om Prakash Dwivedi teaches at Bennett University, Greater Noida. He tweets @opdwivedi82