103 years after the infamous incident, we trace what the Crawling Order was, why it happened and the humiliation Indians had to face.

The incident of the “Crawling Lane” is usually noted in passing when historians discuss the atrocity of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. But the barbaric punishment meant for Indians by General Reginald Dyer in the form of the “Crawling Order” gives us vivid insights into imperial British atrocities in colonial India. After 103 years of the infamous incident, The Sunday Guardian traces what was the “Crawling order”, why it happened and what level of humiliation people had to face for a week.

The whole episode started with the arrest of pro-Indian independence leaders Dr Satyapal and Saifuddin Kitchlew on 11 April 1919; like other Punjab cities, crowds protested in large numbers in Amritsar. On that day, Miss Marcella Sherwood, an elderly English missionary who was a resident of Amritsar for over 15 years, was attacked while she was travelling through a narrow lane known as Kucha Kurrichhan. A violent crowd hit her in the head and when she started to run she was again attacked, and she fell. It made her health condition critical. She was rescued with the help of a few Indians and after initial treatment, sent to England.

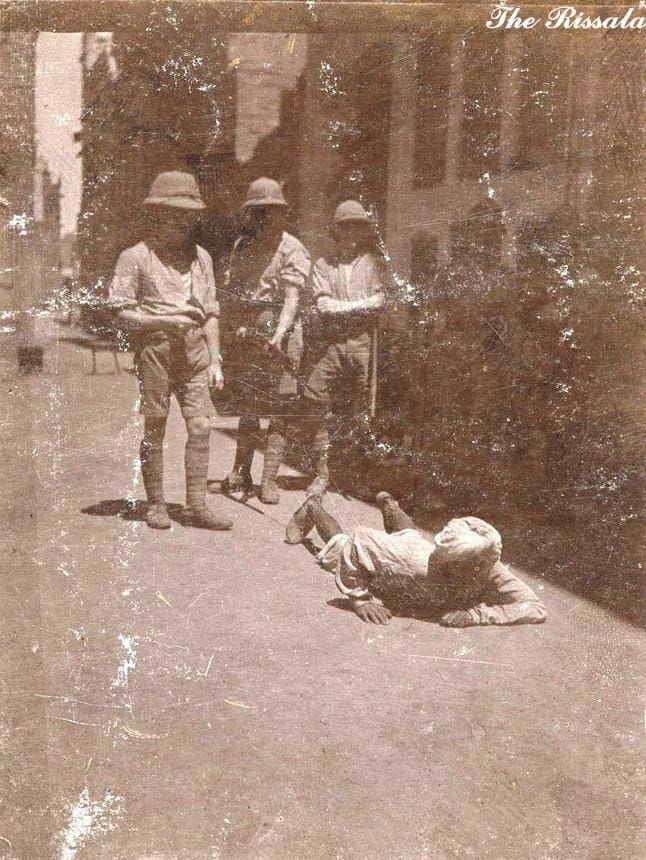

Next two mornings were quiet for the district of Amritsar which was then a part of Lahore division. What happened on 13 April is well documented and called national shame, the massacre at the Jallianwala Bagh. After six days of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, on 19 April, General Reginald Dyer came up with the infamous “Crawling Order”, which was effective for a week. Dyer asked his lower rank officials to place a flogging booth in the middle of the lane where Marcella Sherwood fell after being attacked and both ends of the street—roughly 180 metres long—were encircled by British soldiers, who were strictly ordered that no one should be allowed to walk through the 180 metre long stretch. Anyone who would pass through it, needed to crawl. The soldiers were directed by Dyer to whip those who are not able to pass through the lane crawling.

“The archival evidence shows that people were made to crawl on their bellies and not on their knees. More than 100 people were forced to crawl on their bellies. When a British commission which was appointed on the Punjab massacre asked General Reginald Dyer about the crawling order, he justified it saying that “as many Indians crawl face downwards in front of their gods. I wanted them to know that a white British woman is as sacred as a Hindu god, and, therefore, they have to crawl in front of her, too”. “This also shows the psychological mindset of Britishers about Indians,” said Sumit Kumar, an associate professor of Modern Indian history at the University of Delhi.

The infamous episode which was a dark spot even among all the atrocities committed by Britishers had also been discussed widely in Indian literature. Writers and poets have written extensively about Dyer›s “Crawling Order”. Ghulam Abbas, a famous short story writer from British Punjab, had written Raingneywale (those who crawled) in which he described in detail about how barbaric and inhuman was the order given by General Dyer. Abbas described it as one of the most humiliating crimes committed by Britishers in colonial India. But as it is said in history, time heals everything; people of Punjab have now almost forgotten the “Crawling order”.